* John Akomfrah in conversation with Tina Campt, Ekow Eshun, and Saidiya Hartman, on Akomfrah and the Black Audio Film Collective’s Handsworth Songs (1986) and other subjects; chaired by Ekow Eshun, hosted by Lisson Gallery, London, New York, Shanghai, 18 June 2020

++++++++++

“The future is a slippery project. What can it hold?”

—Erica Hunt

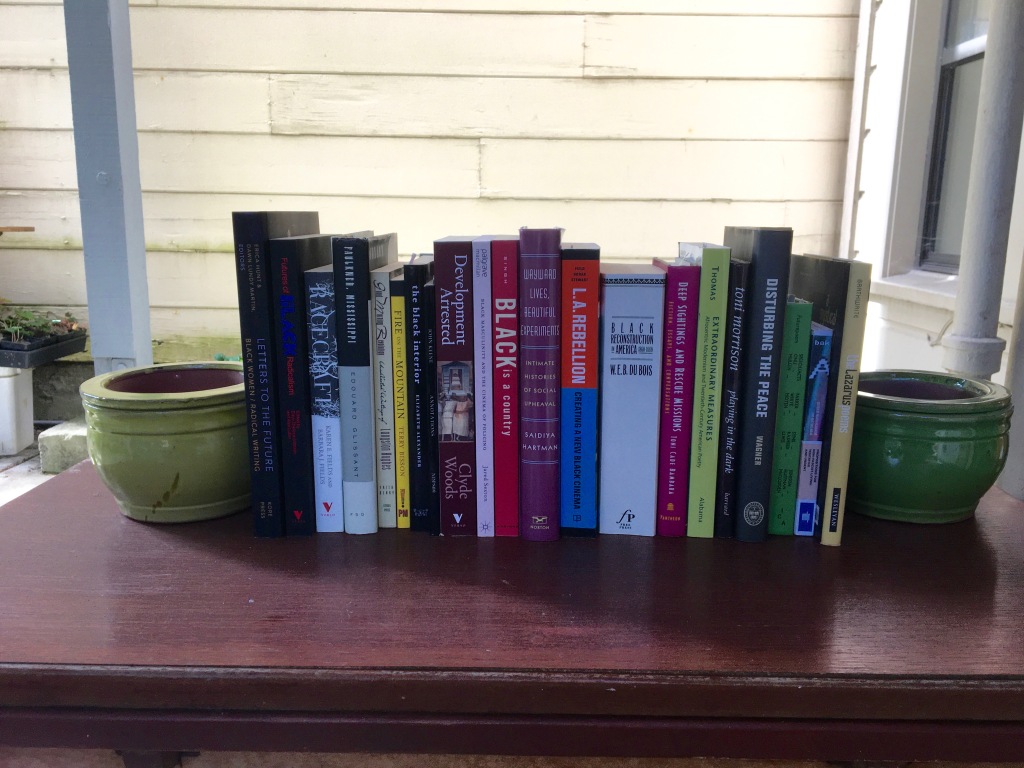

• Erica Hunt & Dawn Lundy Martin, editors. Letters to the Future: Black Women / Radical Writing. Kore Press. Tucson. 2018.

“The future is a slippery project. What can it hold? We asked writers to write about it, imagining the future as the present conjugated—conjoining the past, the present with some other time. Don’t writers write, intuitively, to the future all the time?” — Erica Hunt, Introduction: Angle, Defy Gravity, Land Unpredictably

“It has always been difficult for me to conceptualize what we call Blackness in relation to human bodies, particularly myself as an indicator of the thing I don’t quite understand. It’s a strange predicament, and a worrying one.” —Dawn Lundy Martin, Introduction: Destructions of [The Yoke of It All]

• Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin, editors. Futures of Black Radicalism. Verso. London, New York. 2017.

“The last line in the essay quoted above was penned in the pall of the lynching of Emmett Till, as well as the promise of the mid-twentieth-century Civil Rights movement. The story was about a brutal murder of a Black child and the denial of justice in the aftermath. In looking for the antecedents of Black radicalism, we should consider our individual moments of awakening.” —Cedric J. Robinson, Preface

“Amid a global wave of uprisings, Black protest against police repression and security regimes in the United States has reoriented a conversation about anti-Black racism on an international scale, generating new narratives of struggle and revealing the persistence of racial capitalism and its assault on dispossessed and working people around the world.” —Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin, Introduction

“…In looking for the antecedents of Black radicalism, we should consider our individual moments of awakening.”

—Cedric J. Robinson

• Karen E. Fields and Barbara J. Fields. Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life. Verso. London, New York, 2014.

“During the 2008 presidential election campaign, hardly a week passed without a reference to America’s ‘post-racial’ society, which the election of Barack Obama supposedly would establish…. Right through the campaign, references to ‘race’ and the ‘race card’ kept jostling the ‘post’ in ‘post-racial.’ When insinuations about Obama’s supposed foreignness cropped up, one journalist called that ‘the new race card.’ In fact, it is among the oldest and more durable. Pronouncing native-born Americans of African descent to be aliens goes as far back as Thomas Jefferson and the other founders….

How and why a handful of racist notions have gained permanent sustenance in American life is the subject of this book.” — Karen E. Fields and Barbara J. Fields, Introduction

• Edouard Glissant, translated by Barbara Lewis and Thomas C. Spear. Faulkner, Mississippi. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. New York. 1996.

“She calls my attention to how much (in the pictures in the magazine) the two writers look alike. Both men have an expression that is not haughty but very reserved. They stare straight at you. One is utterly calm, the other withdrawn as if into a dream of greatness….

Both of them are authors of the Plantation; they are two men on the edge of a caste, in a space where all is about to crumble, two colonials in fact, but so marginal among their own kind, two poets concerned with the relentless question of race and the stormy connection of one race to the other you have dominated for so long.” —Edouard Glissant [on Saint-John Perse and William Faulkner], Chapter 1, The Road to Rowan Oak

• Langston Hughes, edited by Faith Berry. Good Morning Revolution: Uncollected Writings of Social Protest by Langston Hughes. Citadel Press. New York. 1992.

“This collection of prose pieces and poems by Langston Hughes has an important purpose—to reestablish firmly and irrevocably a dimension to the genius of Hughes that well-meaning critics and literary historians have ignored (or been ignorant of), blurred, or purposefully eroded.” —Saunders Redding, Foreword

“Langston Hughes was best known as a folk poet, pursuing the theme ‘I, too, sing America.’ But that image, which he accepted but did not choose, is only part of his legacy.” —Faith Berry, Introduction

Good morning, Revolution:

You’re the very best friend

I ever had.

—Langston Hughes

• Terry Bisson, with a new introduction by Mumia Abu-Jamal. Fire on the Mountain. PM Press. Oakland. 2009.

“I am, by any measure, a sci-fi head…. few works have moved me as deeply, as thoroughly, as Terry Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain.” —Mumia Abu-Jamal, Introduction

“In 1859 the abolitionist John Brown, fresh from a successful guerilla war that kept Kansas from entering the Union as a slave state, attacked the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, with a small force of armed men. Brown came to Virginia to fulfill a lifelong dream: to carry the war against slavery ‘into Africa’ (as he put it) by putting a small army of runaway slaves[ and abolitionists onto the Blue Ridge, and heading south…. He had raised funds to buy the most modern weaponry, and recruited the experienced Black slavery-fighter, Harriet Tubman, to be his second-in-command.

…[E]ven in their failure, their raid terrorized the South, electrified the nation, and precipitated the Civil War, which broke out less than a year later.

Fire on the Mountain is a story of what might have happened if John Brown’s raid had succeeded.” —Terry Bisson, prefatory note

• Elizabeth Alexander. The Black Interior. Graywolf Press. Saint Paul. 2004.

“’Today as the news from Selma and Saigon / poisons the air like fallout,’ wrote the poet Robert Hayden in the late 1960s, ‘I come again to see / the serene great picture that I love.’” —Elizabeth Alexander, Preface

“At the heart of this essay is a desire to find a language to talk about ‘my people.’ ‘My people’ is, of course, romantic language, but I keep returning to it as I think about the videotaped police beating of Rodney King, wanting the term to reflect the understanding that ‘race’ is a complex fiction but one that, needless to say, is perfectly real in at least some significant aspects of our day-to-day lives.” —Elizabeth Alexander, ‘Can You Be BLACK and Look at This?’: Reading the Rodney King Video(s)

“…‘race’ is a complex fiction but one that, needless to say, is perfectly real in at least some significant aspects of our day-to-day lives.”

—Elizabeth Alexander

• John Keene. Annotations. New Directions. New York. 1995.

“Such as it began in the Jewish Hospital of St. Louis, on Fathers’ Day, you not some babbling prophet but another Negro child, whose parents’ random choices of signs would disorient you for years. It was a summer of Malcolms and Seans, as Blacks were transforming the small nation of Watts into a graveyard of smoldering metal. A crueler darkening, as against the arrival of dusk. Selma-to-Montgomery…..” —John Keene, Notes, Inscribed Initially in the Narrow, Running Margin

“When I first read John Keene’s fiction…I knew immediately that I was in the presence of genius.” —Ishmael Reed

• Clyde Woods. Introduction by Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta. Verso. London, New York. Second edition 2017.

“Clyde Adrian Woods left us long before anyone was ready to see him go. The last time we met face to face was outdoors in the Southern California sunshine, where the matte effect of Inland Empire smog softens wrinkles and other signs of wear. Nearly three months to the day before he died, Woods spoke mainly about his life’s future purpose.” —Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Introduction

“The establishment of the Lower Mississippi Delta Development Commission (LMDDC) [in 1988] marked the beginning of a new era for the poorest and the most heavily African American region in the United States. The official goal of the commission was to design a ten-year development plan to eliminate the most profound features of economic exhaustion and human desperation. Yet the social origins, organizational practices, and public policies of the LMDDC ensured that the people of the seven-state Delta region would remain mired in a seemingly bottomless state of crisis.” —Clyde Woods, Chapter 1, What Happens to a Dream Arrested?

• Jared Sexton. Black Masculinity and the Cinema of Policing. Palgrave Macmillan/Springer International Publishing. Cham, Switzerland. 2017.

“Black Masculinity and the Cinema of Policing offers a critical survey of the contemporary field of images of black masculinity in early twenty-first century United States. It argues that popular representations of black masculine authority have become increasingly important to the cultural legitimization of executive power within the national security state and its leading role in the maintenance of an antiblack social order forged in the epoch of modern racial slavery.” —Jared Sexton, Preface: The Perfect Slave

“…the lesson, if we can call it that, is in the constellation as it is assembled, the tension that obtains in the space outlined by connecting the dots. Temperament, after all, is not simply an index of the dominance of one of the humors over the others—or, as it happens, one pairing over the others. It signifies the attempt, always incomplete, always impossible, to find some creative way to balance oneself along the lines running between them.” —Sexton, on Moonlight, dir. Barry Jenkins

“In America, ‘Black’ is a country.”

—LeRoi Jones

• Nikhil Pal Singh. Black Is a Country: Race and the Unfinished Struggle for Democracy. Harvard University Press. Cambridge. 2004.

“In America, ‘Black’ is a country.”

—LeRoi Jones, Home: Social Essays

epigraph to Singh’s book

“Martin Luther King Jr. announced his opposition to the Vietnam War in the spring of 1967. In the court of public opinion, the response was swift—he was vilified. King’s decision to break his long silence about the war was overshadowed by his assassination one year later…. The man who only a few years earlier had been charged with saving the soul of America was readily cast beyond the borders of acceptable discourse.” —Nikhil Pal Singh, Introduction: Civil Rights, Civil Myths

• Saidiya Hartman. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. W. W. Norton. New York. 2019.

“At the turn of the twentieth century, young black women were in open rebellion. They struggled to create autonomous and beautiful lives, to escape the new forms of servitude awaiting them, and to live as if they were free. This book recreates the radical imagination and wayward practices of these young women by describing the world through their eyes. It is a narrative written from nowhere, from the nowhere of the ghetto and the nowhere of utopia.” —Saidiya Hartman, A Note on Method

“…It is a narrative written from nowhere, from the nowhere of the ghetto and the nowhere of utopia.”

—Saidiya Hartman

• Allyson Nadia Field, Jan-Christopher Horak, Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, editors. L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema. University of California Press. 2015.

“…I started getting interested in the whole idea of how film was really a ritual and a spell. I’ve noticed that a lot of subliminal images were threaded throughout films in the history of filmmaking and all those things were to the demise of my culture. So I felt I had to work against that kind of symbology and we had to change the ritual. So that’s why I ended up on that road of really seeing filmmaking as a way of emancipating the image.”

—Ben Caldwell, epigraph to the Introduction

“The group of Black filmmakers that have come to be known as the L.A. Rebellion created a watershed body of work that strives to perform the revolutionary act of humanizing Black people on screen…. This first group of film school-trained Black filmmakers shared a desire to create an alternative—in narrative, style, and practice—to the dominant American mode of cinema, an unwelcoming and virtually impenetrable space for minority filmmakers that routinely displayed insensitivity, ignorance, and defamation in its onscreen depictions of people of color.” —Field, Horak, Stewart, Introduction: Emancipating the Image, The L.A. Rebellion of Black Filmmakers

• W. E. B. Du Bois. Introduction by David Levering Lewis. Black Reconstruction in America: an essay toward a history of the part which black folk played in the attempt to reconstruct democracy in America, 1860–1880. The Free Press. New York. 1935, 1992.

“Three weeks before the 1909 annual American Historical Association meeting, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, then a professor at Atlanta University, informed Harvard historian Albert Bushnell Hart that he could not ‘afford the expense of coming north’ to present his paper that December.” —David Levering Lewis, Introduction

“Easily the most dramatic episode in American history was the sudden move to free four million black slaves in an effort to stop a great civil war, to end forty years of bitter controversy, and to appease the moral sense of civilization. From the day of its birth, the anomaly of slavery plagued a nation which asserted the equality of all men, and sought to derive powers of government from the consent of the governed. Within sound of the voices of those who said this lived more than half a million black slaves, forming nearly one-fifth of the population of a new nation.” —W. E. B. Du Bois, Chapter I. The Black Worker

“…Can the planet be rescued from the psychopaths?”

—Toni Cade Bambara

• Toni Cade Bambara. Edited and With a Preface by Toni Morrison. Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions: Fiction, Essays, and Conversations. Pantheon Books. New York. 1996.

“Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions is unlike other books by Toni Cade Bambara…. of her books published by Random House (Gorilla, My Love, The Seabirds Are Still Alive and Salt Eaters) only this one did not have the benefit, the joy, of a series of ‘editorial meetings’ between us.” —Toni Morrison, Preface

“I want to talk about language, form, and changing the world. The question that faces billions of people at this moment, one decade shy of the twenty-first century, is: Can the planet be rescued from the psychopaths?” —Toni Cade Bambara, Language and the Writer

• Lorenzo Thomas. Extraordinary Measures: Afrocentric Modernism and Twentieth-Century American Poetry. University of Alabama Press. Tuscaloosa and London. 2000.

“The subtle analytical powers that enable a poet to comment on life seldom guide her ambition—which, presentation copy in hand, hastens toward any presumably literate being.

Thus Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) reached Thomas Jefferson’s desk. He did mention the book in his writings but not in a way that would have pleased the poet.” —Lorenzo Thomas, Introduction

• Toni Morrison. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, London. 1992.

“These chapters put forth an argument for extending the study of American literature into what I hope will be a wider landscape. I want to draw a map, so to speak, of a critical geography and use that map to open as much space for discovery, intellectual adventure, and close exploration as did the original charting of the New World—without the mandate for conquest…. My work requires me to think about how free I can be as an African-American woman in my genderized, sexualized, wholly racialized world. To think about (and wrestle with) the full implications of my situation leads me to consider what happens when other writers work in a highly and historically racialized society.” —Toni Morrison, 1. Black Matters

“…My work requires me to think about how free I can be as an African-American woman in my genderized, sexualized, wholly racialized world.”

—Toni Morrison

• Bryan Wagner. Disturbing the Peace: Black Culture and the Police Power After Slavery. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, London. 2009.

“Perhaps the most important thing that we have to remember about the black tradition is that Africa and its diaspora are older than blackness. Blackness does not come from Africa. Rather, Africa and its diaspora become black during a particular stage in their history. It sounds a little strange to put it this way, but the truth of this description is widely acknowledged. Blackness is an adjunct to racial slavery.” —Bryan Wagner, Introduction

• Meg Onli, editor. Speech / Acts. Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania. Futurepoem Books. New York. 2017.

“In Black Chant: Languages of African-American Postmodernism (1997), Aldon Nielsen makes a significant contribution to discussions of African American literary production by supplying a literary history for alternate traditions of African American poetry…. The aesthetic and intellectual practices of these writers and their readers enable them to explore the possibilities and limits of prevailing discourses and arm them with the flexibility to be interrogative as well as declarative.” —Harryette Mullen, The Cracks Between What We Are and What We Are Supposed to Be: Stretching the Dialogue of African American Poetry

• Maria Hlavajova and Wietske Maas, editors. Propositions for Non-Fascist Living: Tentative and Urgent. BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, and MIT Press. Cambridge, London. 2019.

“You can imagine it is difficult for those of us coming out of the black radical tradition to embrace the currently popular timeline on fascism. If fascism is back, when did it go away? In the 1950s, with Apartheid and Jim Crow? In the 1960s and 1970s? Not for Latin Americans. In the 1980s? Not for Indonesians or Congolese. In the 1990s? The decade of intensified carceral state violence against black people in the United States?… [W]e can say something about the fundamental difference between common life and undercommon living precisely because we adhere to the black radical tradition’s expanded sense of fascism’s historical trajectory and geographical reach.” —Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, Plantocracy or Communism

“…If fascism is back, when did it go away? In the 1950s, with Apartheid and Jim Crow?… In the 1990s? The decade of intensified carceral state violence against black people in the United States?”

—Stefano Harney and Fred Moten

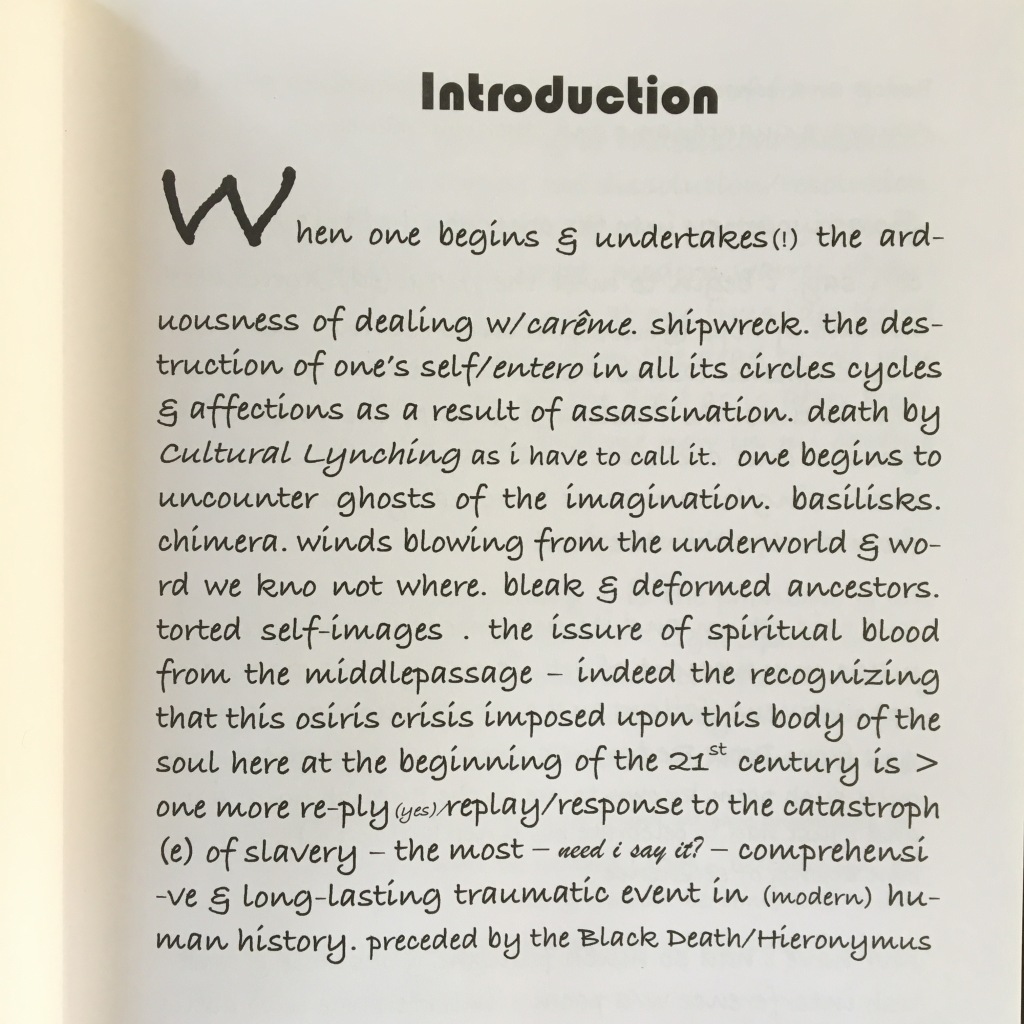

• Kamau Brathwaite. The Lazarus Poems. Wesleyan University Press. Middletown CT. 2017.

++++++++++